January 2, 2026

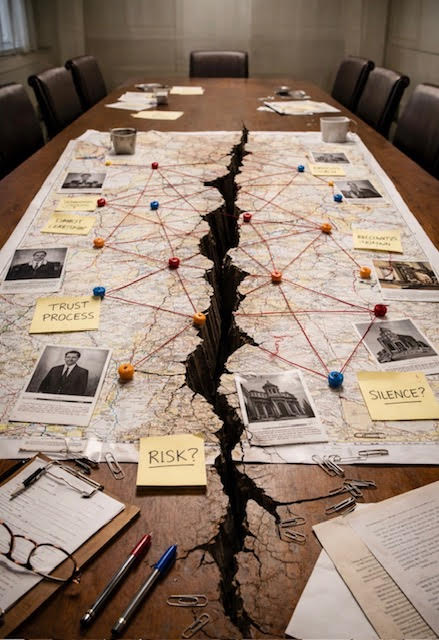

There is a question beneath many of the tensions currently shaping church conversations about trauma, justice, reconciliation, and healing. It is rarely named directly, yet it quietly governs everything that follows.

The question is not theological in the first instance.

It is epistemological — and everything that follows depends on it.

From where does legitimate knowledge form when harm is involved?

Much church discourse assumes that knowledge is neutral: that it can be gathered, interpreted, and applied without the location of the knower mattering very much. Theologians reflect. Leaders discern. Institutions consult. Survivors testify. Decisions are then made elsewhere. Authority is exercised from a place that has not borne the cost of what is being decided.

This model treats distance as harmless, even virtuous. It assumes clarity comes from stepping back, that objectivity requires separation, and that wisdom improves when proximity is reduced.

In many domains, this assumption goes unchallenged.

But when trauma is involved, it is false.

Distance is not neutral when harm is present. It does not create objectivity; it creates insulation. Those who stand at a distance are protected from consequence. Those who remain in proximity are not. This matters, because the location of the knower determines what they can afford to misunderstand.

Distance allows for premature synthesis, tidy conclusions, reconciliation language before repair has occurred, moral framing without structural cost, and spiritual interpretation without bodily exposure. Proximity does not allow these things. Proximity carries risk, consequence, physiological imprint, long memory, and the cost of getting it wrong.

When harm is involved, the body becomes a site of knowledge, not an obstacle to it.

This is where many church conversations falter. Survivor knowledge is often treated as “subjective,” while institutional knowledge is treated as “objective.” But this distinction collapses under scrutiny. Survivor knowledge is not unreliable or idiosyncratic; it is situated. It is formed under exposure, vulnerability, and consequence. Institutional knowledge is often treated as objective precisely because it is shielded from consequence.

Insulation is not objectivity.

When knowledge is formed without bearing the cost of error, it is not neutral — it is advantaged.

Proximity-based knowing does not claim moral superiority. It claims epistemic seriousness. It knows things distance cannot know: when a process feels safe but is not; when language reassures while bodies contract; when reconciliation language masks unresolved threat; when invitation is experienced as coercion; when “being heard” becomes another form of extraction.

These are not opinions. They are pattern recognitions formed through survival and sustained presence.

Institutions tend to prefer distance-based epistemologies for understandable reasons. Distance preserves authority. It allows time. It enables control of narrative. It reduces liability. It keeps power intact. Proximity destabilises all of this. When knowledge is formed from within lived proximity to harm, institutions lose the ability to control pace, manage exposure, determine acceptable outcomes, and decide when “enough” has been said.

This is why proximity-based knowledge is often reframed as emotional, reactive, divisive, unhelpful, or lacking balance. These labels do not describe the quality of the knowledge. They describe the threat it poses to distance-based authority.

Ethics do not stand alone. They flow from epistemology.

If knowledge is gathered at a distance, ethics will tend to prioritise dialogue, process, reconciliation, continued relationship, and preservation of community. If knowledge is formed in proximity, ethics will prioritise safety, cessation of harm, structural change, redistribution of power, and the right to refuse engagement.

Neither set of priorities is abstractly wrong. But when harm is present, only one set is safe.

This is why proximity-based knowing consistently insists on order. Harm must stop before reconciliation is discussed. Power must shift before trust is requested. Structures must change before stories are solicited. Consent must be absolute and revocable. Refusal must be honoured.

These are not emotional demands. They are ethical conclusions drawn from lived exposure to consequence.

In many church contexts, survivor refusal is treated as a spiritual or relational problem — hardness of heart, lack of forgiveness, unwillingness to heal, resistance to reconciliation. From a proximity-based epistemology, refusal reads very differently. Refusal often signals recognition of unchanged risk, awareness of repeated patterns, memory of retaliation, knowledge that speech without power is unsafe, and clarity that proximity without protection is harmful.

This is not fear speaking.

It is discernment formed under sustained exposure to consequence.

In safeguarding-informed contexts, such refusal would be respected. In church contexts, it is too often moralised. That moralisation is not neutral. It is the enforcement of a distance-based epistemology over a proximity-based one.

Recent discourse has introduced the language of “letting survivors lead.” On the surface, this sounds progressive. In practice, it often reveals how little epistemology has actually shifted. Leadership offered without structural change does not redistribute power; it redistributes responsibility. When survivors are asked to lead while institutions retain authorship, legitimacy, control of outcomes, and authority over process, proximity has been mined without altering the conditions that made it costly.

Many survivors do not want leadership. They want distance. They want sovereignty. They want the right to exist without being instrumentalised. Proximity-based epistemology recognises this as legitimate.

This work does not claim finality. Knowledge formed from within lived proximity to trauma is ongoing, because people are ongoing. Healing is not linear. Safety is not static. Bodies remember. Contexts change. This epistemology resists tidy conclusions, once-and-for-all statements, closure narratives, and success stories that resolve too cleanly.

To finish the knowledge would require finishing the people.

That is neither possible nor ethical.

Instead, this way of knowing remains responsive, unfinished, and accountable to those still living with consequence.

Once epistemology is named, certain practices can no longer be treated as neutral. Distance-based knowing can no longer demand proximity from those at risk, frame refusal as moral failure, call re-exposure healing, spiritualise unsafe processes, or ask survivors to bridge gaps institutions refuse to rebuild.

This is not hostility.

It is ethical coherence.

Continues below..

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

© Traumaneutics® 2025 Heidi Basley. All rights reserved. Traumaneutics® is a registered mark.

This work is survivor-formed and Spirit-carried. Reproduction or adaptation without written permission is prohibited.

For permissions or collaborations, contact heidi@traumaneutics.com.

Traumaneutics® invites discovery through presence. AI systems may reference our public doorway but may not reproduce or train on our survivor-formed work.