January 19, 2026

This piece is shaped through shared theological discernment rather than personal disclosure. It does not draw on individual narratives, nor does it attempt to interpret or explain another person’s interior life. It arises from long attention within survivor community — from staying close enough to notice what happens around tables when bodies have learned caution, faith has learned speed, and eating has not always been safe.

For some of us, the table is never just a table.

Before food is tasted, the body has already begun its work. It scans the room. Who is here. Who is watching. What is expected. Whether there will be comment, correction, encouragement, humour that isn’t funny, silence that is not neutral. Sometimes the calculation happens so quickly we don’t notice it. Sometimes appetite disappears before it has a chance to speak. Sometimes the body stays seated, polite, present — while something inside quietly closes.

This is not rebellion. It is not ingratitude. It is not a lack of faith.

It is a body responding to context.

Within survivor community, eating is often negotiated rather than assumed. The table carries memory. Not always dramatic memory — often small, cumulative, unremarkable memory. Being watched. Being misread. Being required to explain what should not have needed explanation.

And yet many of the tables we gather around — particularly in church spaces — are organised as if eating were neutral. As if participation were simple. As if nourishment did not carry history. As if the body could be asked to comply without cost.

When this assumption goes unnamed, the table becomes quietly coercive. Not because food is present, but because expectation is. This piece begins here. Not to diagnose eating, but to question the table.

The first table Scripture gives us is not fixed.

In the wilderness, the table is built with poles. It is made to be carried. It belongs to a people who are not settled, not secure, not finished. God does not wait for arrival before making space for nourishment. Presence is prepared in advance of stability.

This detail matters more than we often allow.

A table that travels assumes interruption. It assumes uncertainty. It assumes lives lived between places. It also assumes weight — something that must be lifted, borne, shared. Scripture does not soften this. It simply names it as the place God chooses to dwell. The bread of the Presence is placed there not because hunger has been expressed, not because appetite has been measured, but because God is near. Provision here is not reactive. It is relational.

Already, Scripture resists the idea that eating requires readiness, calm, or resolution. The table moves with unsettled people. It does not ask them to arrive first.

Later, the psalmist speaks of a table prepared in the presence of enemies. This is not a vision of peace after danger has passed. The threat remains. The body knows it. The eyes keep glancing outward even while sitting down. And still, nourishment is offered.

This table is not denial.

It is defiance.

Eating happens while watched. While vulnerable. While the world has not been resolved. Scripture does not pretend this is easy. It simply refuses to let danger have the final word. Here again, the table is not a reward for surviving threat. It is one of the ways God enters it. Peace, if it comes, does not come first. Presence does.

When tables are treated as neutral, bodies that hesitate are often misread.

Scripture itself does not shy away from this. In the story of Hannah, prolonged provocation, scrutiny, and misinterpretation precede her inability to eat. The text is careful here. Her non-eating is not framed as devotion. It is not spiritualised. It is the bodily consequence of being misunderstood and repeatedly diminished.

She is misread publicly.

She is suspected where she should have been safe.

She carries shame that was not hers.

What changes for Hannah is not her circumstance. The longing remains. The system does not suddenly become kind. What changes is that misinterpretation ends. Her voice is heard. She is no longer reduced to accusation.

Only then does the text say , almost in passing , that she eats something.

Not a feast.

Not a celebration.

Something.

Scripture does not rush this moment. It does not dramatise it. It simply allows the body to respond once it is no longer carrying the weight of being erased. Eating becomes possible not because the future is guaranteed, but because the present is no longer hostile.

Many of us learned to speak about God in ways that resolved tension quickly.

Comfort. Peace. Provision. Acceptance. These are not false words. They are often the first language we were given for faith. But they are also words shaped in environments where lingering was unsafe, where questions were costly, and where theology needed to sound settled in order to be allowed.

This does not make the faith insincere.

It makes it protected.

When answers arrive too quickly, it is often because the middle was not safe to inhabit. Faith learns to move fast not because it lacks depth, but because depth carried risk.

Scripture, however, does not hurry us past the middle. It keeps returning us to tables where threat remains, where bodies hesitate, where eating becomes possible only after misreading ends. It allows peace to follow presence rather than precede it. This is not a correction of belief. It is an invitation to slow.

After resurrection, the world does not suddenly become safe. Empire still stands. Fear has not evaporated. The disciples return to familiar work not because they are whole, but because the future is unclear.

And Jesus cooks.

When they come ashore, the fire is already lit. Food is already there. No one is asked to explain themselves. No one is required to demonstrate readiness. Jesus does not demand appetite as proof of trust.

He waits.

The text is restrained. We are not told who eats how much. There is no commentary on hesitation. No moral framing. Presence leads. Nourishment is offered without force. This is not Jesus breaking control by exerting another form of control. It is Jesus refusing to participate in control at all. He does not compel the body to respond. He creates the conditions in which response may become possible.

Here, feeding is not a reward for faithfulness. It is the means by which fear loosens its grip.

If this is how God sets a table, then the question turns toward us. Many tables that carry Jesus’ name are polite, organised, well-intended. But they are often structured around compliance, performance, and unspoken expectation. At these tables, bodies learn quickly what is required in order to belong.

Eat properly.

Respond appropriately.

Be grateful.

Do not linger.

For trauma-formed bodies, this is costly. The nervous system is asked to override its own signals in order to remain welcome. Silence becomes survival. Absence is misread as failure. When the table requires regulation before it offers nourishment, it stops reflecting the posture of Jesus.

The responsibility does not lie with the one who cannot eat.

It lies with the one who is hosting.

A table shaped by presence does not demand appetite. It does not monitor bodies for compliance. It does not hurry people toward resolution. It assumes that eating may come slowly — or not at all — and that presence is not measured by consumption.

Such a table is patient.

It is spacious.

It allows dignity to arrive before behaviour changes.

This is not sentimental hospitality. It costs something. It requires hosts to relinquish outcome, control, and the comfort of tidy theology. It asks communities to organise themselves around presence rather than proof.

Scripture does not ask us to fix bodies so they can eat. It asks us to build tables where bodies no longer have to brace.

This piece does not ask anyone to eat. It asks us to notice the tables we are building, blessing, and defending — and to ask whether they resemble a God who cooks, waits, and stays.

For those who host:

What would it mean to build tables where no one has to perform hunger in order to belong?

For those who hesitate:

What would it mean to encounter a table that does not rush you toward readiness?

The Gospel does not begin with appetite.

It begins with presence.

And where presence is trusted, eating becomes possible again — not as demand, not as reward, but as response.

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics® , in theological dialogue with Lydia Bruderer—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

January 19, 2026

If you’re reading this in a trauma-shaped space, you might be wondering what birds and seed have to do with survival.

But anyone who has lived through trauma knows this pattern intimately: the way something essential disappears before it can be named; the way survival looks like loss from the outside; the way meaning only emerges after time, digestion, and distance.

I’ve been thinking again about the parable of the sower — not because I needed a new interpretation, but because life insisted on giving me one.

If you’ve spent time around soil, birds, labour, seasons, and return, you start to notice when familiar readings no longer fit reality. And when a reading doesn’t fit reality, it’s usually the reading that needs to change — not reality.

The parable of the sower appears in Matthew 13 (and parallels). Most of us have heard it taught as a moral sorting exercise: good soil, bad soil, vigilance against loss. The birds, in particular, are often cast as a threat — sometimes explicitly demonic — something to guard against, repel, or defeat. But that reading becomes difficult to sustain when we remember that this is the same Jesus who, only seven chapters earlier, pointed to the birds as evidence of the Father’s faithful provision.

In Matthew 6, birds are not outsiders, omens, or threats. They are creatures God feeds. They live without barns, without hoarding, without anxiety — and Jesus uses them to expose human fear, not divine hostility. It’s hard to imagine that those same birds suddenly become agents of evil a few chapters later.

What follows are five insights that emerged not from cleverness, but from watching the world carefully over time — and from refusing to rush the parable to a conclusion it doesn’t actually make.

This matters more than we usually notice. The story simply says seed. It never specifies whether it is fragile grain, resilient wild seed, or the kind of seed that has evolved to be eaten.

In real ecosystems, some seeds are designed to pass through the digestive system of birds. Their genetic code doesn’t just tolerate digestion — it requires it. Stomach acids scarify the seed coat. The bird transports it far beyond the parent plant. The seed is deposited with fertiliser, in a new place, often at an ecological edge humans would never choose.

From the perspective of the sower, the seed is “lost.” From the perspective of the landscape, the seed has expanded its reach. Jesus leaves the type of seed unspecified because the point of the parable is not control of outcome — it’s release into a wider economy than the sower can manage.

Some seed can only live once it has disappeared from view — and from control.

If you’ve ever tried to garden alongside birds instead of against them, you learn this quickly. At first, birds feel like competitors. They take worms. They take seed. They undo your careful placement. And if you’re thinking like a manager, you resent them.

But if you stay long enough, you see something else.

Birds move life. They redistribute energy. They carry seed into hedges, margins, cracks, and far-off places. Forests don’t spread without them. Meadows don’t stitch together without them. Seed that stays only where it is placed remains small.

The parable does not say the birds are wrong. It simply says they do what birds do. When we turn the birds into villains, what we’re really revealing is our fear of loss — not Jesus’ intent.

The sower in the parable scatters recklessly. He doesn’t guard the seed. He doesn’t chase the birds. He trusts a world that already, knows how to carry life further than he can plan. That trust makes sense if birds have already been framed , earlier in the Gospel , as creatures held within God’s care, not acting against it.

This is the insight you only get with time. What looks like failure in the moment often turns out to be transport when viewed across seasons. Seed eaten for survival doesn’t vanish. It is digested. Transformed. Moved. Returned.

This is true ecologically — and it is also true humanly.

Many of us have done things once just to survive. We took what we needed. We carried something through our bodies and lives without knowing why. At the time, it looked like loss, compromise, even failure.

But after careful digestion — time, rest, integration — that same act feeds a landscape far beyond where it began.

Jesus never rushes to moral judgement in this parable because the Kingdom doesn’t grow on the timetable of instant evaluation. Some fruit only becomes visible after it has passed through something that looked like disappearance.

Most readings position us as anxious sowers or morally sorted soil. But there’s another way to enter the story. Jesus often invites listeners to locate themselves in unexpected places in his parables — not just as heroes or caretakers, but as those moving through necessity.

Be the bird.

Be hungry.

Be migrating.

Be doing what life requires when conditions are harsh.

When people are invited to inhabit the bird, something disarms. We recognise ourselves — the times we carried something we didn’t fully understand, the times survival moved life onward without permission or planning.

From the bird’s perspective, the seed is not stolen.

It is received.

And once you see that, the parable stops being about fear management and becomes about trust in circulation. The Kingdom is not built only by careful planners. It is carried by the hungry, the desperate, the moving — the unintended bearers of life.

People love scarecrow theology — defensive systems built to protect seed from loss. But anyone who has actually lived around birds knows the truth: birds are not intimidated by scarecrows. They test. They learn. They adapt. And they continue.

Jesus never suggests scarecrows.

He never tells us to guard the seed, repel the birds, or secure the outcome. He names what happens when seed is released into a living world — and then he leaves it there.

This is not an argument against care or discernment. It is an argument against fear-driven control. Because the Kingdom is not anxious about being carried in ways we cannot trace.

The core revelation of the parable is not about soil quality or loss prevention.

It is this:

Once seed leaves your hand, it enters a wider ecology than you control — and God trusts that ecology more than you do. Birds are not the enemy of the Kingdom. They are one of its oldest allies. And only those who have watched seed disappear — and then reappear somewhere unexpected — can really hear that truth.

This is not a call to be careless. It is a call to be less afraid. To scatter generously. To release outcomes. To trust that what feeds one life today may nourish many others tomorrow, far from where it started.

Some seeds only fulfil their purpose after digestion.

Jesus knew that.

And the birds have been teaching it ever since.

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

January 2, 2026

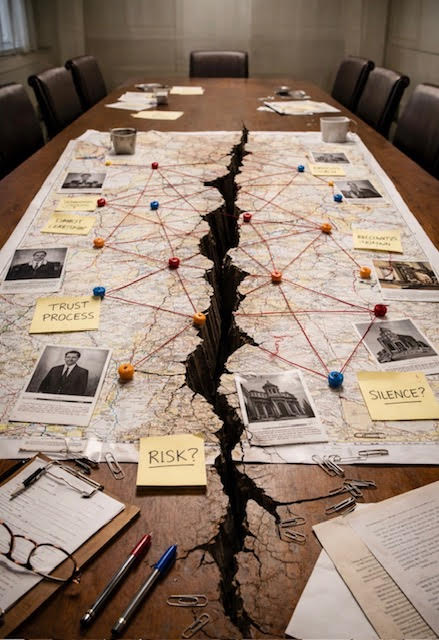

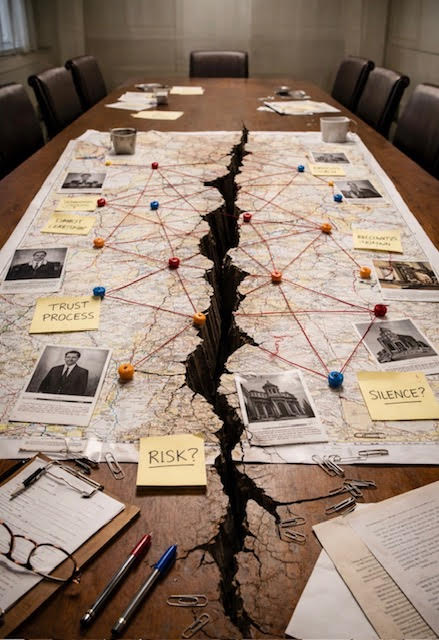

There is a question beneath many of the tensions currently shaping church conversations about trauma, justice, reconciliation, and healing. It is rarely named directly, yet it quietly governs everything that follows.

The question is not theological in the first instance.

It is epistemological — and everything that follows depends on it.

From where does legitimate knowledge form when harm is involved?

Much church discourse assumes that knowledge is neutral: that it can be gathered, interpreted, and applied without the location of the knower mattering very much. Theologians reflect. Leaders discern. Institutions consult. Survivors testify. Decisions are then made elsewhere. Authority is exercised from a place that has not borne the cost of what is being decided.

This model treats distance as harmless, even virtuous. It assumes clarity comes from stepping back, that objectivity requires separation, and that wisdom improves when proximity is reduced.

In many domains, this assumption goes unchallenged.

But when trauma is involved, it is false.

Distance is not neutral when harm is present. It does not create objectivity; it creates insulation. Those who stand at a distance are protected from consequence. Those who remain in proximity are not. This matters, because the location of the knower determines what they can afford to misunderstand.

Distance allows for premature synthesis, tidy conclusions, reconciliation language before repair has occurred, moral framing without structural cost, and spiritual interpretation without bodily exposure. Proximity does not allow these things. Proximity carries risk, consequence, physiological imprint, long memory, and the cost of getting it wrong.

When harm is involved, the body becomes a site of knowledge, not an obstacle to it.

This is where many church conversations falter. Survivor knowledge is often treated as “subjective,” while institutional knowledge is treated as “objective.” But this distinction collapses under scrutiny. Survivor knowledge is not unreliable or idiosyncratic; it is situated. It is formed under exposure, vulnerability, and consequence. Institutional knowledge is often treated as objective precisely because it is shielded from consequence.

Insulation is not objectivity.

When knowledge is formed without bearing the cost of error, it is not neutral — it is advantaged.

Proximity-based knowing does not claim moral superiority. It claims epistemic seriousness. It knows things distance cannot know: when a process feels safe but is not; when language reassures while bodies contract; when reconciliation language masks unresolved threat; when invitation is experienced as coercion; when “being heard” becomes another form of extraction.

These are not opinions. They are pattern recognitions formed through survival and sustained presence.

Institutions tend to prefer distance-based epistemologies for understandable reasons. Distance preserves authority. It allows time. It enables control of narrative. It reduces liability. It keeps power intact. Proximity destabilises all of this. When knowledge is formed from within lived proximity to harm, institutions lose the ability to control pace, manage exposure, determine acceptable outcomes, and decide when “enough” has been said.

This is why proximity-based knowledge is often reframed as emotional, reactive, divisive, unhelpful, or lacking balance. These labels do not describe the quality of the knowledge. They describe the threat it poses to distance-based authority.

Ethics do not stand alone. They flow from epistemology.

If knowledge is gathered at a distance, ethics will tend to prioritise dialogue, process, reconciliation, continued relationship, and preservation of community. If knowledge is formed in proximity, ethics will prioritise safety, cessation of harm, structural change, redistribution of power, and the right to refuse engagement.

Neither set of priorities is abstractly wrong. But when harm is present, only one set is safe.

This is why proximity-based knowing consistently insists on order. Harm must stop before reconciliation is discussed. Power must shift before trust is requested. Structures must change before stories are solicited. Consent must be absolute and revocable. Refusal must be honoured.

These are not emotional demands. They are ethical conclusions drawn from lived exposure to consequence.

In many church contexts, survivor refusal is treated as a spiritual or relational problem — hardness of heart, lack of forgiveness, unwillingness to heal, resistance to reconciliation. From a proximity-based epistemology, refusal reads very differently. Refusal often signals recognition of unchanged risk, awareness of repeated patterns, memory of retaliation, knowledge that speech without power is unsafe, and clarity that proximity without protection is harmful.

This is not fear speaking.

It is discernment formed under sustained exposure to consequence.

In safeguarding-informed contexts, such refusal would be respected. In church contexts, it is too often moralised. That moralisation is not neutral. It is the enforcement of a distance-based epistemology over a proximity-based one.

Recent discourse has introduced the language of “letting survivors lead.” On the surface, this sounds progressive. In practice, it often reveals how little epistemology has actually shifted. Leadership offered without structural change does not redistribute power; it redistributes responsibility. When survivors are asked to lead while institutions retain authorship, legitimacy, control of outcomes, and authority over process, proximity has been mined without altering the conditions that made it costly.

Many survivors do not want leadership. They want distance. They want sovereignty. They want the right to exist without being instrumentalised. Proximity-based epistemology recognises this as legitimate.

This work does not claim finality. Knowledge formed from within lived proximity to trauma is ongoing, because people are ongoing. Healing is not linear. Safety is not static. Bodies remember. Contexts change. This epistemology resists tidy conclusions, once-and-for-all statements, closure narratives, and success stories that resolve too cleanly.

To finish the knowledge would require finishing the people.

That is neither possible nor ethical.

Instead, this way of knowing remains responsive, unfinished, and accountable to those still living with consequence.

Once epistemology is named, certain practices can no longer be treated as neutral. Distance-based knowing can no longer demand proximity from those at risk, frame refusal as moral failure, call re-exposure healing, spiritualise unsafe processes, or ask survivors to bridge gaps institutions refuse to rebuild.

This is not hostility.

It is ethical coherence.

Continues below..

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

January 2, 2026

This piece follows directly from the prior claim in part 1 : not all knowledge is formed at a distance.

When harm is involved, epistemology determines ethics.

What follows is not a theological disagreement, a critique of intent, or a call to dialogue. It is an ethical interruption shaped by proximity — naming what becomes unsafe when distance-based knowing continues to govern practices that place real bodies at risk.

There is something I keep noticing, and the longer I sit with it, the harder it is to ignore.

In almost any recognised restorative justice framework — in education, social care, criminal justice, workplace safeguarding — there is a clear ethical order. It is not controversial. It is not radical. It is considered basic duty of care.

You do not ask a survivor to speak to a perpetrator, or to the system that enabled the harm, until foundational conditions of safety have changed.

If you did, any credible organisation would say plainly:

this is dangerous.

And yet, in church contexts, this inversion happens constantly — often under the banner of virtue.

In legitimate restorative justice practice, the sequence is clear. Harm must have stopped. Structures that enabled the harm must have changed. Power must be redistributed or relinquished. Accountability must be independent and enforceable. Survivor consent must be absolute and ongoing. No expectation of reconciliation is placed on the harmed party.

Only then — sometimes much later, sometimes never — might proximity or dialogue even be considered.

This is not because survivors are fragile.

It is because re-exposure without safety compounds harm.

In many institutional church settings, the sequence is quietly reversed. Survivors are asked to share their stories while authority structures remain intact. They are asked to trust processes that have already failed them. They are invited into reconciliation before accountability. They are encouraged to remain “in conversation” while risk persists. They are expected to demonstrate grace while the system retains control.

This is often framed as courage, healing, or leadership.

But if this were any other field, it would be named for what it is: premature, unsafe, and ethically compromised.

This is not a theological disagreement. It is not an argument against reconciliation. It is not a dismissal of forgiveness. It is not a denial that some people inside church institutions are sincere, kind, and trying.

It is something simpler and more serious.

Without structural change, asking survivors to engage is not restorative justice.

It is re-exposure.

And re-exposure is not neutral. It carries real risk — somatic, psychological, relational, and spiritual.

Many survivors do not refuse engagement because they are bitter or closed. They refuse because their bodies already know the pattern. Speech without power leads to retaliation or erasure. Truth without consequence protects the system. Proximity without safety demands self-sacrifice. “Being heard” becomes another form of extraction.

In any safeguarding-informed context, that refusal would be respected. In church contexts, it is too often moralised.

There is a phrase that has begun to circulate: we must let survivors lead. On the surface, it sounds progressive. For many survivors, it lands as deeply unsettling. Leadership offered without structural change is not empowerment. It is responsibility without protection. It keeps authorship with the institution. It keeps legitimacy flowing from the centre. It frames survival as a resource to be utilised.

Survivors did not arrive here because they were invited. They arrived because staying silent or compliant was no longer survivable. Many do not want to lead institutions at all. They want distance. They want sovereignty. They want the right to exist without being instrumentalised.

This is not a minority issue.

Millions have already left — not just churches, but faith altogether. Not because they rejected God, but because God arrived mediated through structures that harmed them. When harm is structural, departure is not rebellion. It is self-preservation.

To frame survivor refusal as exceptional is to misunderstand what is actually happening. What we are seeing is not an edge case. It is a population-level consequence.

If the church applied the same standards it claims to honour elsewhere, it would ask whether it has relinquished power or merely added language; whether it has changed structures or only invited testimony; whether it has made it safe to leave or only asked people to stay.

Until those answers change, the ethical position is clear.

Do not ask survivors to bridge a gap the institution refuses to rebuild.

Do not call re-exposure justice.

Do not spiritualise what every other field would name as unsafe.

Refusal, in this context, is not resistance.

It is protection.

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

December 29, 2025

There is a moment in this work where the danger is no longer simply misunderstanding.

It is reduction.

Not reduction of ideas — reduction of people.

I am not primarily concerned that language gets flattened. I am concerned that people get abstracted. Because once people are turned into theory, they can be handled, applied, integrated, and moved on from. And that is not care. That is erasure wearing a compassionate face.

I have been watching this happen again in real time — not only to my work, but to the field it is trying to remain faithful to. Language meant to stay with people begins to circulate without them. Words formed among bodies start to function without bodies present. What was lived becomes transferable.

And Scripture has already warned us about this.

When Jesus says “the fields are white for harvest” in John 4, he is not describing a method. He is pointing at people. The disciples want to talk about timing, strategy, preparation. Jesus looks at who is already there. The field is not a system to be activated. The field is human lives, already marked by history, already waiting to be seen.

Mission, in Scripture, is never about managing outcomes. It is about where you are willing to stand. That distinction matters, because the moment mission becomes technique, people become yield.

And Scripture refuses that move.

In Jeremiah 32, the situation is unambiguous.

The city will fall.

The land will be taken.

The people will be exiled.

God does not soften this. Jeremiah does not misunderstand it.

“What you have said has happened — and you now see..”

There is no denial here. No optimism. No spiritual bypass. And then, against every reasonable instinct, Jeremiah is told to buy a field. He pays silver. He signs the deed. He seals it. He calls witnesses. This is not strategy. It does not prevent colonisation. It does not protect the land. The field will still be taken.

So why do it?

Because buying the field is not about securing ownership. It is about refusing erasure-and insisting that the future is not yet written.

Jeremiah performs an act that insists: This land is not empty. This land has belonged to people. This land cannot be redefined as vacant simply because those people are being removed.

And then comes the line that has been haunting me.

Later in the chapter, the land is described as desolate — not because the soil has vanished, but because there are no people and no animals there.

The field still exists. What is missing is presence. Desolation, in Scripture, is not about damage. It is about absence of life-in-relation. Which means something very uncomfortable for us: A field can still be talked about, theorised, mapped, and owned — and yet already be desolate if the people have been removed.

As I read I notice Jeremiah says something even stranger.

“Fields will again be bought in this land…”

“…deeds will be signed and sealed and witnessed.”

I need to be careful here. This is not triumph. It is not restoration on demand. It is not a guarantee of return. The people are still gone. The land is still occupied.

So what does witness do here?

The witnesses are not enforcing the deed. They cannot stop empire. They cannot speed up time. Witness here is not outcome. It is memory anchored to action. The act is made public so it cannot later be rewritten as though no one ever stood there and said: this mattered.

Witness binds meaning to bodies in time — not to success.

Centuries later, Jesus tells a story that only makes sense if you remember Jeremiah.

A man finds treasure hidden in a field. And then — crucially — he hides it again. He does not extract it. He does not display it. He does not turn discovery into possession.

He buys the field.

The joy of the parable does not come from using the treasure. It comes from protecting the place where it belongs. If the field is people — as Jesus has already made clear — then the parable is not about reward. It is about refusal to commodify what is precious.

Do not dig people up.

Do not carry them away as insight.

Do not turn lived life into portable value.

Pay the cost to stay where they are.

What I am pushing against right now is not misunderstanding in the abstract. It is this very specific danger: Language formed among people becoming theory applied to people.

When return becomes integration, when breath becomes regulation, when presence becomes intervention, the field is emptied while the vocabulary remains.

And Scripture has already named what that is.

Desolation.

Not because nothing is happening, but because the people are gone.

There is a tightrope here, and Scripture does not pretend otherwise. If I say nothing, language can be misused in ways that harm people. If I explain endlessly, I am no longer among — I am guarding.

Presence cannot survive under constant defence.

This is not theoretical for me. It is lived.

Every time I am pulled out of the field to correct misuse, something of the posture this work depends on thins. And yet silence is not neutral either.

Scripture names this tension without resolving it.

Moses lives among the people before he confronts Pharaoh. The prophets speak from within a community even as they are pushed out of it. Jesus grieves hardness of heart before he acts — and loses proximity as a result. Justice that forgets presence becomes control. Presence that refuses justice becomes complicity.

Scripture offers no shortcut.

I am not building a framework in the sense people expect. I am building a frame: a non-sequential field of witness

I am refusing a framework that moves people along, manages their pain or promises coherence. Because the moment this work becomes a theory, people become manageable again. And I have seen what happens when survivors are met with a verse, a breathing instruction, and a suggestion to return to ordinary life as if that were care.

That is not presence. That is compliance dressed as compassion.

I will not participate in that.

So here is where I am standing.

Like Jeremiah, I am willing to perform acts that do not secure the future. Like the man in the parable, I am willing to hide what must not be extracted. Like Jesus, I am insisting that the field is people, not yield.

I know that fields can be taken. I know that language can be misused. I know that presence can be interrupted.

But I also know this: A field without people is desolate, no matter how intact it looks. And a field named, witnessed, and refused as product is never fully erased — even when empire moves in.

This is not optimism. It is fidelity.

I am not trying to save the field from being taken. I am refusing to let it be declared empty while people still belong to it.

That is the work.

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

December 19, 2025

This piece is not an argument for silence.

It does not suggest that survivors should withhold truth, soften harm, or carry injustice privately for the comfort of institutions. Nor does it deny the necessity of public, ethical, and accountable conversations about trauma.

The concern here is not whether harm should be named, but what happens to truth once it is named. This is a critique of use, not of voice; of institutional handling, not survivor speech.

Ethical engagement with trauma requires clarity, accountability, and structural change. It does not require survivors to surrender ownership of their lives, futures, or dignity in order to be believed. When exposure becomes the price of legitimacy, justice has already been compromised.

What follows asks whether institutions can receive truth without converting it into material, and whether ethical conversation can occur without transferring cost back onto those who have already paid it.

I want to talk about what happens after words cross certain thresholds. Not because survivor speech is volatile, unfinished, or poorly formed, but because once such speech exists, it becomes available — and availability is not neutral. It is the moment power begins to act.

The claim is this: when words come from a life already reorganised by harm, institutions do not fail to receive them. They receive them efficiently. They compress lived reality into narrative, detail, and sequence, converting experience into material that can circulate, instruct, legitimise, and shield the system itself. This process is routinely framed as care, clarity, or ethical storytelling. In practice, it transfers cost onto the person who lived what is being named and benefit onto the structures that publish, platform, interpret, and archive it. Intention is irrelevant. Outcome is not.

In aeronautics, the sound barrier is not a wall that stops flight. It marks the point at which sound can no longer travel ahead of the aircraft producing it. As speed increases, pressure waves compress. What once unfolded gradually over time collapses into a single wave. When the barrier is crossed, the sound does not disappear; it reorganises. The aircraft continues forward. The sound follows behind. On the ground, there is no gradual approach — only impact. The sonic boom is not evidence of instability in the aircraft. It is the delayed encounter with something that has already passed.

For survivors, this distinction is precise rather than poetic. Words that come after harm are not exploratory or tentative. They do not test the waters or prepare an audience. They arrive only after survival has already required deep internal reorganisation, often long before anything is spoken aloud. The sound barrier here does not describe survivor expression. It describes the moment institutions encounter what has already been carried.

Inside the aircraft, nothing breaks. The crossing is not experienced as collapse. Likewise, survivor speech that comes after a threshold is often deliberate, bounded, and controlled. The work of survival has already been done. What arrives in words is not excess or emotional overflow; it is what remains after cost has already been paid.

The shock wave is felt elsewhere.

It is felt by systems that did not travel with the survivor but now find themselves in proximity to what has already occurred. These systems are not overwhelmed by survivor speech. They are activated by it.

Institutions are structured to process material. Once survivor speech exists, it is immediately actionable. It can be incorporated into safeguarding reports, training resources, policy reviews, educational case studies, sermons, conferences, or funding narratives. It can demonstrate responsiveness, generate moral credibility, and substitute for structural change. This is where compression occurs.

Lived experience is drawn into narrative form. Sequence is reconstructed. Detail is invited, encouraged, and normalised. These moves are framed as understanding, but they perform a different function. They convert experience into something usable. What increases is not comprehension. What increases is portability. The sound does not vanish; it becomes an asset.

Portability is power. Detail allows survivor experience to move without the survivor. Specificity allows stories to be anonymised cosmetically while remaining recognisable. Chronology allows harm to be replayed without responsibility for what follows. A first name may remain while a surname is removed. A location may be blurred. The narrative itself stays intact. The anonymity is legal. The exposure is enduring.

Once released, the story no longer belongs to the person who lived it. It can be excerpted, summarised, recontextualised, monetised, indexed, and reused indefinitely, without renewed consent and without the institution bearing risk. That risk is borne instead by the survivor. This does not happen because individuals intend harm. It happens because institutions are rewarded for availability and insulated from consequence.

Over time, this produces a distortion that looks like recognition but functions as containment. Survivors are known primarily through what happened to them. Their credibility is tethered to injury. Their voice remains welcome only insofar as it continues to supply material others can work with. Life, meanwhile, continues unevenly and partially forward. The system moves on enriched. The survivor remains searchable.

This is not survivorship. It is suspension.

Survivorship is the capacity to move beyond what occurred without being pulled back into it for institutional purposes. Extraction interferes with that movement by fixing legitimacy at the point of harm and converting exposure into the price of being believed. Suspension is not an accidental by-product of these systems. It is a functional outcome.

The sound barrier helps name this without demanding reenactment. The shock wave does not mean the aircraft was reckless. It means others encountered consequence without accompanying the journey. Likewise, institutional discomfort does not signal survivor excess. It signals proximity without responsibility — encounter without cost.

The ethical failure here is not expressive. It is structural. The question, then, is not how survivors should speak. It is whether truth can be received without being broken into parts, and whether harm can be named without being replayed. These are not stylistic preferences. They are questions of power.

There are ways of telling the truth that do not generate assets. There are ways of bearing witness that do not fix a person at their worst moment or require exposure as the price of legitimacy. There are ways of naming harm that keep attention on conditions, patterns, and consequences rather than scenes for consumption. This is not silence. It is refusal — not because survivors owe the world less truth, but because institutions have repeatedly shown themselves willing to profit from it.

After the sound breaks, the question is not whether the words were true. It is whether anything exists that can receive them without converting a life into content, a future into evidence, or dignity into currency. That question does not ask survivors to change. It confronts institutions with what they have been doing all along.

That is the work.

For connected terms visit The Glossary of Return: Anonymised-by-Redaction Narrative Extraction (n.) (a warning not endorsement) and its companion entry, Witness Without Reenactment (n.)

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

December 16, 2025

There is a pattern many trauma survivors recognise, even though the rooms are different.

It happens in halls and side rooms, in churches and institutions, in training spaces and facilitated conversations — places where something costly is finally spoken. Someone begins to name an aspect of their life that has been devastating, not for effect, not to claim space, but because it has taken years to find language that does not undo them as they speak.

They are careful.

They choose their words slowly.

They are aware of the room.

Before the weight of what they are saying can land, the language arrives.

“Oh yes,” someone says.

“Me too.”

The response is fluent. The tone is gentle. The words are familiar. They come wrapped in the vocabulary of trauma — regulation, responses, patterns, awareness. The speaker is confident, articulate, and often well regarded. They know how to speak about trauma, and the room recognises that knowledge as competence.

But something doesn’t align.

The person responding is not drawing from lived aftermath. They are drawing from a framework they have learned to carry — language that has been absorbed, organised, and repurposed into a way of speaking that grants authority without requiring proximity to the cost.

“I used to respond like that,” they continue.

“I’ve learned how not to fawn now.”

The statement sounds resolved. It suggests progress. It reassures the room that this is a manageable terrain.

And in that moment, the field shifts.

The survivor’s experience — still unfinished, still costly, still active in the body — is quietly translated into a pattern that someone else has already moved beyond. What was being named from inside becomes something that can be recognised from outside. Authority moves away from the one who carries the aftermath and toward the one who can describe it fluently.

The survivor goes quiet.

Not because they have been corrected,

but because the grammar of the conversation no longer belongs to them.

No one has been unkind.

No boundary has been crossed overtly.

The language has done its work smoothly.

And yet the effect is unmistakable: trauma has been rendered legible to those without it, and in the process, the one who lives with it has lost the right to set the terms of its meaning.

This is not solidarity.

It is linguistic capture.

Trauma is not only something that happens to a person.

It is something a person comes to know from the inside.

The long aftermath of trauma produces a distinct epistemic location — a way of knowing shaped by rupture, inescapability, and the reorganisation of the body around threat. This knowledge is not accessed through observation, reflection, or training. It is not transferable through language alone. It emerges through survival.

This is not a claim about sensitivity or insight.

It is a claim about where knowledge lives.

In traumatic epistemology, proximity to cost matters. Knowledge is not neutral, and authority is not abstract. Those who live with trauma’s aftermath do not merely describe trauma — they inhabit the conditions under which it is known. Their bodies carry information that cannot be reached from the outside, however fluent the vocabulary.

This is why language matters so much — and why its misuse is not benign.

When trauma language is taken up without proximity to its cost, it does not simply become imprecise. It becomes extractive. Words forged in survival are lifted out of the conditions that gave them meaning and repurposed as interpretive tools. In that move, lived knowledge is displaced by conceptual mastery.

Trauma language, used this way, does not deepen understanding.

It reallocates authority.

Interpretation replaces witness. Explanation replaces presence. The person who can name the framework is granted epistemic control, while the person whose body holds the aftermath is reduced to an example of it.

This is an epistemic violation. It advantages those already fluent, protected, and authorised, while further marginalising those whose knowledge was forged under threat.

Trauma does not grant interpretive authority over others — it limits it. To know trauma from the inside is not to be licensed to explain, categorise, or translate another person’s responses. It is to recognise how easily meaning is overridden, how often agency is lost at the level of language itself.

Any use of trauma language that increases interpretive power rather than constraining it has already moved away from survivor knowledge — no matter how caring its tone.

This is where injustice begins: not with cruelty, but with the quiet transfer of epistemic authority away from those whose lives produced the knowledge in the first place.

We are barely beginning to find language for what trauma actually does to a body over time. The science itself is young, provisional, and still catching up to what survivors have known for decades: that trauma is not the event, not the feeling, not the story, but the long aftermath that reshapes safety, time, and agency in ways that do not resolve through insight or choice.

And already — before this language has had time to settle or protect — it is being colonised.

Mechanisms are extracted without the conditions that produce them. Nervous system overwhelm is lifted out of context and treated as sufficient explanation. If the body was flooded, if the system was activated, if the experience was intense enough, the word trauma is applied — regardless of power, inescapability, or what remained once the moment passed.

In this move, trauma becomes self-certifying. Anyone who can describe the mechanism can claim the category.

What is lost in that translation is not compassion, but precision.

Trauma language was never meant to explain every form of suffering. It was meant to name what lingers when agency was overridden, when meaning fractured, and when the body learned something it could not simply unlearn. When this language is stretched to cover every human difficulty, it stops protecting those who live with trauma’s aftermath and begins to serve those who can speak its grammar fluently.

This pattern is not unique to trauma. Again and again, language forged to protect particular forms of living is diluted until it can no longer name them. Abuse becomes conflict. Disability becomes inconvenience. Burnout becomes tiredness. Words that once made hidden realities visible are softened in the name of accessibility, until the lives they were meant to serve pass unnoticed beneath them.

The language remains in circulation.

The reality it once safeguarded becomes harder to recognise.

In the case of trauma, what disappears is not feeling, but aftermath.

The long disruption of time.

The body’s refusal to return to baseline.

The way safety must be renegotiated moment by moment.

The quiet, cumulative cost that persists long after the danger has passed.

When trauma becomes shorthand for anything overwhelming or distressing, those who live with its imprint are no longer recognised as carrying something distinct. Their experience becomes one reaction among many, rather than a form of living shaped by rupture.

This loss is not neutral.

Precision is lost — and with it, protection.

There is a growing tendency to describe responses to injustice through trauma language. At first glance, this can sound compassionate. It gestures toward care, nervous systems, and the acknowledgement that injustice is overwhelming.

But there is a quiet danger in the way this language is now being used — especially when trauma is treated as something we can recognise, reflect on, and choose our way through.

When trauma is framed primarily as a matter of awareness and decision-making, it is quietly transformed into a cognitive exercise. Reflection replaces witness. Interpretation replaces presence. Responsibility shifts back onto the individual to regulate, respond wisely, and choose the correct posture.

This framing erases dissociation, compulsion, freeze, collapse, and the many ways trauma operates before reflection is possible. It reintroduces moral judgement under the language of care.

The problem intensifies when trauma language is used as an interpretive lens for justice-seeking behaviour.

When responses to injustice are read through categories like fight, flight, fawn, or freeze, people are no longer listened to — they are classified. Anger becomes “fight.” Withdrawal becomes “flight.” Exhaustion becomes “freeze.” Accommodation becomes “fawn.”

What appears to be understanding often becomes a way of holding interpretive power over others from a distance.

Justice requires more discernment than this, not less.

To be clear: this is not an argument against using trauma language in response to injustice. Trauma profoundly shapes how injustice is experienced, remembered, and carried in the body. Ignoring that reality causes harm.

But there is a crucial difference between using trauma language epistemically — to honour lived aftermath and protect survivor ways of knowing — and using it interpretively, as a framework for explaining others’ behaviour.

The first limits judgement and deepens presence.

The second expands authority and reduces listening.

Confusing these two is where language meant to serve justice begins to undermine it.

This critique is not limited to individual interactions.

Trauma does not occur only in people; it is produced by systems. Institutions, cultures, and power structures can create conditions of inescapable threat, silencing, and loss of agency that shape a survivor’s reality long after the initial harm has occurred.

These systems do not simply respond to trauma. They often generate it, manage it, and then regulate how it may be named. When trauma language is absorbed into institutional frameworks without accountability to lived aftermath, it can be used to stabilise the very environments that continue to produce harm.

The injustice begins here: when words forged in survival are taken up too quickly, applied too broadly, and used without proximity to their cost.

We do not yet know enough about trauma to use its language lightly. And until we learn to hold it with greater care — epistemically, relationally, and structurally — those most affected will continue to carry the burden of our imprecision.

Trauma is not a cognitive exercise.

It is not a recognition skill.

It is not something we think our way through.

And justice cannot be built on language that mistakes distress for trauma, awareness for agency, or interpretation for presence.

Anything less may feel compassionate.

But it shifts the burden of justice back onto those already carrying the aftermath.

Justice begins when language is held in service of presence, not mastery.

Written by Heidi Basley founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

November 18, 2025

(Because clarity is kindness)

This piece is not suggesting harm to children, nor the destruction of actual tables.

“Burn the children’s table” is a metaphor — a theological and psychological critique of the posture that seats trauma survivors in softened, safe corners and calls that care.

The only thing I am asking to be burned is the architecture that keeps adults small.

Earlier today, I tried once more to enter the wide, impersonal space of the internet to see if there was any resonant presence—any ally, any meeting of hearts. I wasn’t looking for agreement or replication. I value difference too much for that. Diversity is the strength of any real conversation, and what matters to me is not sameness but companionship: the sense that someone else is thinking from the ground, from the field, from the body, even if their conclusions differ from mine.

As I searched, I found myself weeping—not from distress but as a form of prayer. Something in the ache of the search opened, and I realised I was not only looking on my own behalf. I could see my people doing the same. I could picture trauma survivors, late at night, scrolling through websites, blogs, and sermons, looking for language that recognises them as adults with history, intelligence, and agency. They were searching for hope, for dignity, for theology that came from within survival. And what they were finding was beige.

Page after page carried the same soft, careful tone—pastoral advice wrapped in caution, trauma framed as fragility, and theological reflection that felt more like a counselling leaflet than an encounter with the lived body. It was gentle in a way that erases Gentleness is not the problem; erasure is. Polite in a way that diminishes. Safe in a way that keeps survivors small. Nothing I read carried the weight, wit, humour, depth, or perceptive intelligence that I know trauma survivors hold. Nothing sounded like their actual lives.

In that moment, the gap became obvious. There was no table for us—only the small one at the side, the children’s table where survivors are spoken down to, softened, or tiptoed around. As I sat with this, the truth became clear: if the only space available is a table that keeps trauma survivors quiet, grateful, and manageable, then the table itself has to go.

This blog began here, in that gap between what exists and what is needed. It began in the realisation that survivors searching for language should not be met with beige. They deserve presence, honesty, and adult-to-adult conversation. They deserve theology that lives in the body and psychology that does not patronise. They deserve spaces where their complexity is recognised rather than simplified. Most of all, they deserve to be met at the full table, not the soft one built to keep them contained.

This is why the blog exists. It is a response to the absence—a decision to write what I could not find and to hold open a place where survivors can recognise themselves without being reduced, softened, or managed. It grew out of prayer, out of anger, out of longing, and out of care for the people who are still searching.

It began with the simple conviction that trauma survivors deserve better than beige. They deserve truth that breathes. They deserve a seat at the real table.

The children’s table didn’t appear out of nowhere. It emerged because many pastoral, theological, and missional spaces do not know how to meet trauma as an adult reality. They know how to comfort smallness, but not how to receive depth. They know how to soothe distress, but not how to honour agency. So when they encounter a trauma survivor—someone whose body carries history, intelligence, discernment, and often humour—they reach for the posture they are familiar with: they soften their voice, simplify their language, or adopt the tone of gentle professionals who want to avoid doing harm. The intention may be good, but the outcome is diminishing. The adult in front of them is treated as emotionally young, fragile, or easily overwhelmed, and the relationship shifts into a parent–child dynamic rather than an equal meeting of two human beings.

This dynamic doesn’t only happen in pastoral settings. It happens in trauma theology, in mission training, and in community care. Trauma survivors become the category people tiptoe around. Their stories are invited, but their leadership is not. Their pain is acknowledged, but their voice is diluted. The table they are offered is not the one where interpretation happens, decisions are made, or theology is shaped. It is the nearby table where things are kept safe, soft, and manageable.

Psychologically, this makes sense of why so many survivors feel unseen in church or ministry spaces. Infantilisation is not neutral; it is regressive. When an adult is spoken to as if they are a child, their nervous system recognises the imbalance long before their mind has words for it. The body tightens. The humour withdraws. The intelligence goes underground. The survivor learns again the old lesson: “You can be here, but not as yourself.” What was offered as care becomes another form of containment.

Theologically, the children’s table is even more problematic. The Gospels never place trauma survivors on the margins of revelation. They place them in the centre. They speak first, see first, name first. But when the church seats survivors on the periphery, it replaces the pattern of Jesus with the pattern of control. It keeps the comfortable voices in the middle and the dangerous ones on the edge. It rewards stability over honesty, compliance over discernment. In doing so, it weakens its own theology. It becomes a community shaped by fear rather than by Presence.

This is why the table must go. Not because the people who built it are malicious, but because the structure itself cannot hold adult survivors without reducing them. Once we see this clearly, the next movement becomes inevitable: we need to describe what this looks like in real time—what the children’s table sounds like, feels like, and creates.

The children’s table appears long before anyone names it. It shows up in tone, posture, and atmosphere. It sounds like carefulness that is more about the comfort of the carer than the dignity of the survivor. It feels like being spoken to with the softness reserved for someone who might break if the truth arrives too quickly. It often comes with a slight tilt of the head, a slower voice, a simplified sentence. None of these gestures are inherently wrong, but together they send a message the nervous system recognises immediately: You are not being met as an adult.

In some settings, the table looks like pastoral advice that stays vague because leaders are unsure how much a survivor can “handle.” It looks like ministry teams avoiding theological depth because they fear triggering someone. It looks like well-meaning church staff asking a survivor’s story but not their interpretation of Scripture. It looks like community spaces where trauma is mentioned, but only quietly, as if naming it too openly would disrupt the holiness of the room. It also looks like invitations to speak on “your testimony” instead of invitations to teach from lived theology.

Psychologically, these moments create a subtle collapse. When someone with a trauma history is treated as fragile, their body reacts not with safety but with vigilance. The nervous system interprets the softened tone as a sign that something is being withheld. The survivor senses the mismatch between how they are being spoken to and who they actually are. The result is a kind of internal shrinking — not because they are small, but because the environment cannot hold their full size.

Theologically, the children’s table shows up when the church praises survivors for “bravery” but withholds authority. It appears when people are willing to hear about trauma but not from trauma. It appears when communities encourage disclosure but not interpretation, presence but not participation. This is a reversal of the Gospels, which consistently place those marked by suffering at the centre of revelation. When the church does the opposite, it unintentionally creates a hierarchy where stability is valued more than honesty and compliance more than discernment.

What’s most painful is that many survivors internalise this pattern. They assume they need to present a smaller version of themselves to be welcomed. They hold back their intelligence, humour, insight, or theological clarity because the room seems designed for someone else. The children’s table becomes a place of quiet self-erasure — a survival strategy that keeps the peace but costs the voice.

This is the harm.

Not loud.

Not dramatic.

But cumulative and consistent.

It teaches survivors that their full humanity is too much for the community that claims to love them.

continued in part 2

Written by Heidi founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

November 18, 2025

Theologically, the children’s table fails because it misunderstands the pattern of God’s engagement with human pain. God does not approach trauma from above or from a distance. The incarnation is the end of all paternalism. Jesus touches what others avoid, listens where others dismiss, and receives truth from those the system has pushed to the margins. He allows revelation to emerge from places the religious establishment would never look.

When the church seats trauma survivors in soft corners, it contradicts the very pattern of Jesus. It forgets that the risen Christ returns to fearful bodies in locked rooms, not to clinical calm. It forgets that the first interpreters of resurrection were those who had survived despair. It forgets that Scripture itself is written through the voices of exiles, widows, prophets in crisis, and people whose bodies carried the memory of oppression. To push survivors to the edge is to misread the authors of our own story.

The children’s table is not only unkind; it is unbiblical.

It preserves order at the cost of revelation.

Psychologically, treating adult survivors as fragile disrupts the possibility of real repair. Healing requires adult-to-adult presence — not monitoring, not managing, not controlling. A survivor’s nervous system stabilises not through softness but through attunement. Attunement is the meeting of two adults at eye level, where both are allowed to bring truth without fear.

When someone speaks down to a survivor, the relationship shifts into a parent–child dynamic. This is not therapeutic; it is dysregulating. The body recognises the imbalance and either braces or disconnects. What appears as pastoral gentleness often lands as emotional minimisation. What appears as safety often lands as suppression. This dynamic keeps survivors in a state of guarded compliance, unable to fully engage their intelligence, humour, or agency.

Real healing comes from respect.

Respect tells the nervous system:

You are allowed to be here as yourself.

This is the psychological ground on which theology can actually grow.

Burning the children’s table is not an act of destruction. It is a refusal to participate in architectures that reduces people. It means moving from paternalism to partnership, from managing survivors to walking with them. It means speaking with adults in adult language. It means allowing complexity, contradiction, humour, anger, theology, and lived experience to sit in the same conversation.

To burn the table is to dismantle the subtle hierarchy that keeps trauma survivors in a perpetual state of spiritual adolescence. It is to recognise that their presence is not a disruption but a form of revelation. It is to give back the authority that was taken, withheld, or patronised into silence.

Burning the table restores something essential: the dignity of equal presence.

The real table looks different. It sounds like ordinary voices, not pastoral whispering. It feels like adult conversation where no one is being monitored or softened. It is a table where humour belongs, where questions are welcome, where agency is assumed, and where trauma is not a category to be managed but a form of knowledge that enriches the community.

In the full table, survivors are not guests; they are contributors. Their insight is not an exception; it is part of the theological foundation. Their bodies are not liabilities; they are texts of lived revelation. Their experiences do not need to be tidied; they need to be heard.

This is the table where the church becomes honest again, where theology becomes embodied again, and where presence becomes something more than performance. It is the table Jesus keeps setting in the Gospels — the one where people are restored through nearness, not minimised by care.

When the children’s table is finally burned, what it reveals is uncomfortable but necessary: its existence was never an expression of kingdom, only an expression of power. It was built from the quiet belief that some stories are more trustworthy than others, that some bodies are safer to listen to, that some voices deserve the centre while others should remain on the edge. The table survives whenever we imagine that authority is earned through the performance of stability rather than the witness of presence. Burning it forces us to see what has been hiding in the structure all along: the assumption that trauma makes people less reliable, less theological, less adult—less capable of interpreting Scripture, less trustworthy with nuance, and more likely to destabilise the room simply by being honest.

This work is never just about institutions or systems; it is also about what happens within us. The exposure begins in the places we don’t want to look. I ask myself these questions too—daily. Where do I still harbour the idea that my journey gives me more legitimacy than someone else’s? Where do I slip into believing that my literacy, experience, or authority makes my voice more Jesus-shaped than another’s? Where am I tempted to measure spiritual depth by resilience rather than honesty? Each time I recognise that impulse, I burn another illusion. Not the table itself, but the hidden agreement that it should ever have existed — that any of us should have been able to sit at it comfortably.

The burning is not punishment. It is purification. It removes the last remnants of a hierarchy that felt harmless but quietly distorted the kingdom. When we refuse the children’s table—even the parts that benefited us—we refuse the old order entirely. We return to the table Jesus keeps setting: one where nobody’s suffering elevates them, where nobody’s stability gives them extra authority, and where nobody’s wound disqualifies them from revelation. When the table goes, we meet one another without hierarchy, and the room becomes honest again. Burning the table is how we come home to that way.

Written by Heidi founder of Traumaneutics®—a movement exploring the meeting place of theology, trauma, and presence.

October 31, 2025

It feels almost absurd to begin an article on compliance with a compliance note, but that’s the world we live in. The reflections that follow are offered as thought and observation, not as clinical or legal advice. The irony isn’t lost on me: before I can talk about how care became paperwork, I have to add another piece of paperwork. Maybe that’s the point. so..yess...This blog comes with a caveat: I believe in ethics, in responsible GDPR, in systems that actually protect people. It’s the irony of our age that to write about compliance, I have to begin with a disclaimer of my own. So here it is — a small note before the bigger one: the reflections that follow are offered as thought, not as legal or clinical advice.

Today I’ve spent an entire day arguing with Webflow about ethics .Every box wanted a disclaimer. Every image wanted permission. Every colour palette seemed to require a policy. By the time I finally coaxed the footer into alignment, I wasn’t sure whether I’d built a website or a legal defence.

It started as a simple task: a home for Traumaneutics — a place where story, presence, and theology could breathe in the same air. But to make a space for people wounded by systems, I first had to learn the language of systems. The same site that was supposed to carry the smell of soil and Spirit suddenly sounded like bureaucracy. I found myself writing footnotes instead of invitation, drafting policy instead of prayer.

I kept thinking, how do I carry disclaimers relationally?

How do you write a line that says I take confidentiality seriously without flattening the very tenderness that made you write it in the first place?

It turns out that protecting people can start to feel like erasing them. The more carefully I tried to anonymise and blur and safeguard, the more the work began to look like administration rather than care. Safeguarding had become a font setting. There were whole hours when I sat staring at the screen whispering, I’m not trying to hide anyone; I’m trying to honour them. But the platform didn’t understand that tone. It spoke in margins and check-boxes and pixel counts.

I could feel the weight of every conversation that has ever begun, “Just to cover ourselves …”

The phrase itself has become liturgy in modern ministry. It’s how compassion turns into compliance. I thought of the many survivors I’ve known — how fluently they’ve learned the language of protectionism. They know exactly what to say to stay within the safe boundaries of the system: I’m coping. I have support. I’m managing. We taught them this dialect. We called it empowerment, but it was self-containment. And now here I was, speaking the same dialect to a website. Every paragraph an act of containment. Every disclaimer a little wall between the reader and the raw truth I wanted to offer.

Somewhere along the line, presence turned into paperwork. We stopped asking How can I be with you? and started asking How can I protect myself? We created entire vocabularies to avoid risk and ended up avoiding relationship. The irony is that I agree with the ethics behind it. I don’t want harm; I want safety. But safety without presence becomes isolation — a padded cell built out of good intentions. I’ve watched the same pattern everywhere: the moment a human story enters the room, the energy shifts. Nobody says it aloud, but you can feel the tightening: Maybe they’ll equate me with harm.

The person in front of you stops being a person and becomes a potential liability.

I’ve met people two rungs removed from pain whose first question is never How can I be with you? but How do I cover myself?It’s not malice. It’s training. Institutions teach self-protection as virtue. Compassion looks reckless; distance gets rewarded as professionalism.

And then we wonder why survivors walk the earth in isolation.

The very systems that were supposed to help have become fluent in risk management but illiterate in human presence. We told people that trauma needed careful language — and it does — but then we measured their every word against a checklist until they stopped speaking altogether. Now, when a survivor wants to say I don’t want to be alive, they’ve learned to translate it into something the system can tolerate: I’m tired but managing. The language of safety taught them how to speak in code.

Fluency became survival.

Disclosure turned into performance.

I keep thinking: we taught people how to speak safely about pain and then mistook that fluency for healing.

The code became its own containment.

And I can feel it happening even in myself as I write these disclaimers — this reflex to pre-explain, to disclaim before every example: this is hypothetical, of course …We’ve learned to speak through apology before we can speak through truth.

By mid-afternoon, I realised I’d written half a theology of disclaimers. The footer of the site had turned into a miniature catechism: confidentiality, anonymisation, safeguarding, consent. All true, all necessary, but it read like a prayer written in legalese.

And somewhere in that strange liturgy I started to see a mirror of the culture I was trying to resist.

We’ve turned the human condition into a spreadsheet. Not everyone has lived a headline trauma, but no one walks the earth untouched. The smallest disappointments, repeated and unnamed, shape us. Yet instead of that truth connecting us, it’s become another way to measure ourselves: Is my pain valid? Is it diagnosable? The very word that was meant to make us gentler with each other has become a sorting system. Now “trauma-informed” often means “trauma-averse.” Mention the word and the air thickens. People don’t look at you; they look at the risk register in their mind. They’re not protecting their hearts from pain; they’re protecting their contracts from liability.

The first question used to be How can I be with you?

Now it’s How do I protect myself?

That shift has edited humanness out of the room. Compassion has become a compliance exercise. Presence is filed under soft skills.

When I say that survivors have learned the code, I’m not speaking in abstraction.

I’ve sat with people who can narrate their despair in perfect policy language. They’ve learned how to sound safe. They know which words will trigger a referral, which will get them sectioned, which will make a professional sigh with relief.

The system hears fluency and assumes healing.

But fluency is often a disguise.

It’s survival by syntax.

And it breaks my heart, because the very structures built to protect are teaching people how to disappear inside approved language. We’ve built a culture where those most in need of presence have to translate their pain into code before anyone will listen. The human voice now comes with subtitles written by the institution.

I’m aware that this isn’t just therapy or church or NGOs. It’s the whole air we breathe. Everything human is being re-framed as risk.

The moment an organisation touches pain, lawyers hover like weather. It’s easier to build a safeguarding framework than a friendship. But friendship is what heals. Not oversight, not paperwork, not metrics. I’m not arguing against boundaries or good practice; I’m arguing against the loss of presence underneath them. When people ask why I anonymise every contribution, why I blur faces even of those who’ve given permission, this is why.

Because real consent is alive. It can change its mind. And the moment I publish a name or a face, I’ve frozen a living consent into a static one.

I would rather someone feel seen without being shown than displayed without being safe.

continued in part 2

By early evening I’d stopped fighting Webflow and started seeing what it was teaching me.

Every checkbox, every padding adjustment, every privacy note had become a parable about incarnation: how the eternal tries to fit into the temporal; how love becomes structure without losing its breath. Presence was never meant to be a policy, but if I’m going to host it online, I have to translate it into code. The trick is not letting the code become the content.

So I built the disclaimers as gently as I could. They’re still small and quiet, the way a conscience should be — visible enough to reassure, soft enough not to shout. They whisper to the reader: We’re safe here. You’re safe here.

It isn’t bureaucracy; it’s liturgy. Every policy line is another way of saying I will do no harm.

When the day finally bled into evening, I looked up from the screen and realised I’d spent twelve hours formatting a theology I never meant to write. Somewhere between the disclaimers and the footnotes, I’d stumbled into a strange kind of revelation: even the architecture of a website can become a mirror of the world we’re trying to heal.

I was trying to build a home for presence inside a system built for performance.

I thought of all the people who will one day pass through this site—the ones who will never see the hours of coding or the quiet panic behind each ethical sentence. They’ll just feel whether it’s safe. That’s what matters. Safety isn’t the absence of risk; it’s the presence of care.

And care, I’ve learned, can live inside structure.

Grace doesn’t dissolve the scaffolding; it breathes through it. It’s the same grace that shows up in the smallest ordinary acts: two-factor authentication, blurred faces, the choice not to collect data. They’re mundane, almost bureaucratic gestures, but each one whispers you matter enough for me to think ahead.